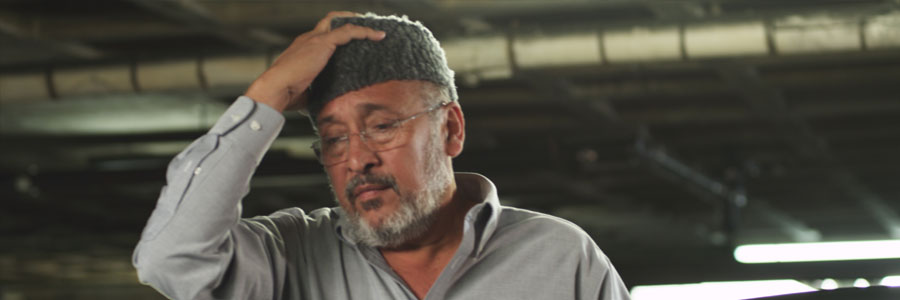

WASHINGTON, DC: Raj Amit Kumar is a filmmaker and founder of Dark Frames, an artists’ collaborative dedicated to producing cinema with a strong socio-political element.

Kumar will release his first film in the United States through Dark Waters — titled “Unfreedom.” Banned in India, the film addresses the trials and tribulations faced by members of the LGBT community in India as well as the harsh realities of Islamophobia.

Kumar graduated from the College of Staten Island with a Masters of Arts in Cinema and Media Studies and began work on “Unfreedom” directly afterward.

Apart from filmmaking, he is also a media academic, college professor, and writer whose writings and research papers have been published and presented at various conferences around the world.

Excerpts of an interview with Kumar:

Your latest release, “Unfreedom,” was banned in India. Why is that?

The film deals with two very important issues that are pressing. One story deals with homosexual identity and what it faces in India. Homosexuality was criminalized in 2013 and the film shows some inherent truths about what LGBT and homosexuals face in India when it comes to brutality, rape, police violence, and certainly other things.

The second place takes place in New York and deals with the Islamophobia that we live in, where more and more the idea is being cultivated that Muslim people are all violent, or all terrorists. In the current wake of fundamentalism religious forces are taking over political control and taking over the consciousness of the country, which I find bothersome. I think that played a major role in the censor board banning my film.

They have asked me to change the film but I am making a stand. I refuse to do a diluted version of the film or my own expression. I have a certain expression and I intend to keep it like that.

We’re going to the high court soon and we will take this to the highest legal authorities to say that it is completely wrong [to censor the film].

“Unfreedom” raises issues of religious fundamentalism and homosexuality; despite the ban on homosexuality in India, people keep coming out and there is a movement by the gay community. Do people get arrested for homosexuality in India?

I don’t think people are getting arrested if they come out, but it’s a very strange way of being. Legally, you’re criminalized for being gay. But they won’t throw you in jail for standing up and saying, “I’m gay.” It is a complicated scenario, though. It means that if — and this happens all the time — if authorities want to use that law to exert force, they are allowed to do so. The law also creates a perception that being gay is something completely evil and wrong.

There are many people who want to embrace it and not all the common people are against it. It seems ridiculous that the government can make a decision like that for the people. I believe in youth, and I believe in progressive thinkers, and I believe there are forces who think we need to move on and move away from the old Victorian moralities and laws that we embraced centuries ago. The religious forces have now gained more political control and financial power and are going to be very averse to that, though.

Hindutva seems to be becoming as much of an evil as Muslim fundamentalism in India – are there a danger to India’s social fabric, what are the long term consequences will be?

We’ve already seen the consequences! In any religion — be it Hinduism, Islam, Christianity, or any other, fundamentalism is the most evil possible thing. Fundamentalism is terrorism, I would say. It’s not Muslim terrorism or Hindu terrorism — fundamentalism is terrorism. You are violently enforcing your rules upon the rest of society and that’s what’s happening in India. It has already happened — we’ve been seeing it over the past ten years. India was one of the most settled countries and still is in many ways — I believe the common people of India are very secular — it’s rooted in us. But this whole wave of fundamentalism took over the whole world.

In 1992 when there were the Hindu vs. Muslim riots, I believe that was the height of it and the entire country was mobilized in the name of Hindu fundamentalism and in the name of these Hindu monsters, if I may say so. The parties who were behind making that happen rule the country now. What that does is gives all the other fundamentalist groups and organizations a confidence that that they can go out there and do anything they want. We are on a very bad path and unless we stand up and speak out against it, we’ll be unable to do anything to change that. It’s the same way with Muslim liberals, I feel the same way– that it is their job to speak up more and more and to express themselves, to say, this is wrong.

With the spread of ISIS and incidents like the killing of the blogger Avijit Das In Dhaka, do you fear making fundamentalism related films?

No, I don’t. It’s like you get afraid to see the world going in a certain direction, or afraid of the state of the world and you get afraid to see how many of us would not have the courage or may not be able to say what we want to say because of what’s happening around us and what these people are trying to do to it.

What is your next feature, Black Boots, about and what else is next for Dark Frames?

My second film is about the first black Marines who went to World War II. Their story was never told; these were called “Montford Point Marines,” and they were sent to segregated boot camps. That created a legacy that has led to the kind of Marine Corps we have today, which is one of deep-seated inequality.

These men received the Congressional Medal [of Honor] in 2012. It took years and years before they got any recognition and it. We’re working closely with the Montford Point Marines Association on the film. The marines are called the Montford Point Marines because that was the name of their camp.

India is so well known for exporting a workforce of the highest caliber in STEM-related fields. Do you believe it can gain the same recognition for the arts?

We have amazing artists and filmmakers, and technicians as well. I think it’s a measure of how the relationship between the two industries are structured. Part of the reason is because it is easier to import works of filmmakers from other parts of the world because they’re basically Hollywood movies already. It’s easier for someone in Hollywood to relate to those films; when it comes to the Bollywood genre, it’s just completely alien filmmaking. It’s not easy for anyone sitting in Hollywood to say, “Someone just made this amazing Bollywood film!” But there are some amazing Bollywood filmmakers.

What is the most difficult challenge facing the furthering of LGBTQ rights and knowledge in India?

The challenge is to battle the past of old Victorian morality and the present forces of Hindu fundamentalism.

Are extremists who wish to stifle freedom of speech emboldened by the right-wing nature of Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s party?

Yes, of course the right wing extremist groups feel that they have much more political and violent power over the country for next five years