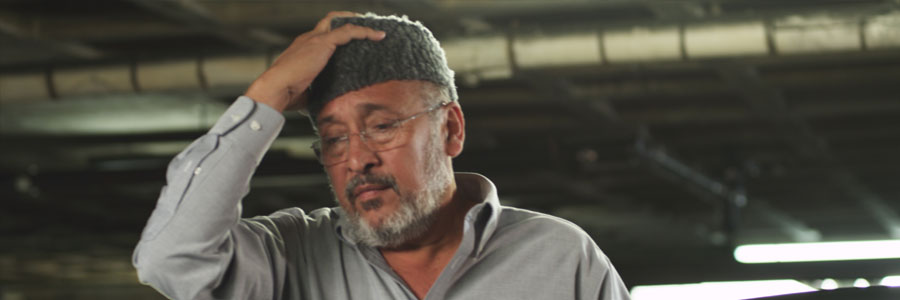

UNFREEDOM. Director: Raj Amit Kumar. Players: Victor Banerjee, Adil Hussain, Bhanu Uday, Preeti Gupta, Bhavani Lee. English and Hindi with Eng. sub-titles. (Dark Frames). Releasing May 29 (Dark Frames Studio).

Extreme viewer discretion advised.

First-time filmmaker Kumar’s debut work Unfreedom marches to the beat of a very different drum. Banned in Kumar’s native India by the national film censoring body on grounds that the film may “ignite unnatural passions,”Unfreedom aims for a highly provocative stance. Disturbingly powerful and violent, even numbingly so at times, Unfreedom tangles with gut-wrenching social riddles about modern India as a dystopian playground for religiosity and homophobia carried out to fascist extremes. While the film is not great, the premise certainly scores big time.

In one of two incongruent stories that Kumar’s script follows, there is Husain (Uday), a young Muslim man arriving in New York from India. He stands on the edge of the water and surveys the best-known skyline in the world. Husain’s face, however, seems unmoved at the sight of the ultimate urban getaway, staring out instead as if seeing nothing but tall blank spaces. Husain’s mission: to track down one Professor Fareed (Banerjee), a renowned scholar whose teachings of a practical, moderate view of all religions, including Islam, poses a threat to Husain’s ideology. A dark force is about to descend again on these shores.

On the other side of the world, Leela (Gupta), a beautiful woman in New Delhi, goes out on a date. The date is not with a brawny beau but with the outspoken and striking artist Sakhi (Lee). The two women meet. They snuggle. They celebrate life and their love for each other. Somewhere in the city, Leela’s father Devraj (Hussain), a ranking police inspector, is firmly, forcefully if necessary, ready to make sure that his daughter remains “unspoiled” by her lesbian identity. A dark force is about to descend on Leela and Sakhi’s surreptitious rendezvous.

Kumar’s settings have a surreal feel. This is especially true in the depiction of India, which here has been transformed into a proto-police state that is increasingly limiting individual liberties, flagrantly disregarding privacy rights and freedom of association. In this environ, the subcontinent is ripe for exploitation by the two common demons from India’s news headlines—religious fundamentalism threatening the world’s largest yet restive democracy and the rights of gays being trampled into the ground as a result of recent decisions by India’s highest judiciary.

When viewed through this surreal prism, the violent content becomes slightly more palpable. The non-violent sexual content comes across as intensely private and unabashedly liberating, in sharp contrast to the violent sexual content which is suffocating at times. There are unimaginable brutalities carried out by Husain after he kidnaps Professor Fareed. On the other hand, Leela’s father may resort to similar violence.

The persecution of lesbians brings to mind Deepa Mehta’s Fire (1996) while the misogyny carries shades of Shekhar Kapur’s Bandit Queen (1994)—coincidentally, works that were also banned in India. In a somber, quirky twist, the most protracted of the several gory scenes also unintentionally bring to fore recent ISIS atrocities in the Middle East —even though the filming of Unfreedomwas completed more than a year ago.

Banerjee’s kidnap victim Fareed has a serene Buddha-like countenance. As a counterpoint, Uday’s Husain is a barbaric brute whose screen genesis is rooted in the likes of Hollywood entries Natural Born Killers (1994) and Taxi Driver(1976). Gupta’s Leela, meanwhile, gradually hardens from a fidgety possible runaway to a steel-willed woman who will stand her ground no matter what. While Lee’s Sakhi goes from outspoken to a determined obstinacy, the real counterpoint to Gupta’s Leela is Hussain as Leela’s father Devraj, whose ingrained family values have him migrating from possible breadwinner-compromiser to Grand Inquisitor.

In Kumar’s Unfreedom, absolute power percolates up to the virtual gods of all passions—be they radicalizing imams in faraway madrassas or institutional misogyny so entrenched and so threatened by the specter of giving a woman the same space to unfurl her privacy as they readily do for a man. These gods then stealthily direct the hand of a brutal jungle “justice” carried out in soft suburban afternoon light.

Kumar gets kudos not for an uneven delivery but for conjuring up a scary, horrible place that thrives on little or no breathing room. Unfreedom offers a great premise in search of a great movie. And even though a self-selected “X–Rated” disclaimer would have been advisable, the bite of Kumar’s social commentary makes it worth seeing.

EQ: B+